when his lamp shone upon my head,

and by his light I walked through darkness

Job 29:3

I don’t remember too many conversations from when I was of primary school age. Two stand out. One was telling the Vicar of my Church of England primary school that the idea of God was made up by the ruling classes to suppress the working classes! The other was far more profound. I must have been around 10 years of age and had gone swimming with my friend Alan at the Serpentine in Hyde Park, London. The conversation turned to people who had drowned in such locations. I said, “I wonder what death is like?” to which my friend replied, “well, it’s all just black, it’s like nothing.” More than any words exchanged, I simply remember the feeling – of being horrified. I guess all of us become aware of our mortality at some point. And most of us try hard to put it out of our minds and distract ourselves. I duly did this too, filling my life with football, music, girls and books on history and politics.

I am currently reading a book called ‘The Shattering of Loneliness’ by Erik Varden, Bishop of Trondheim in Norway. I am stuck on chapter one, I can’t move beyond it at present. This is not because I don’t like the book but that I am struggling to digest its content. It is either closed on my desk or I am reading over a certain section again.

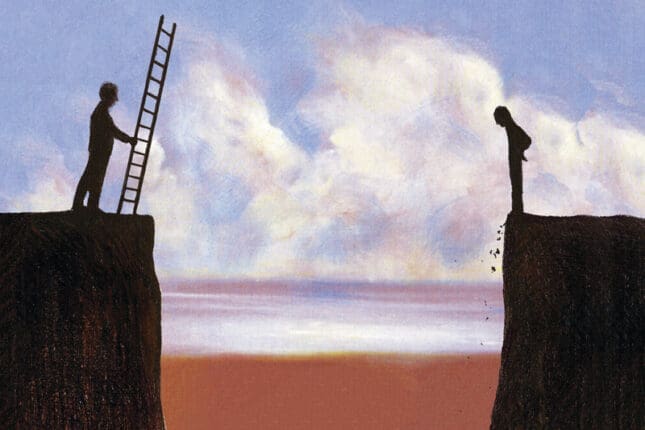

In reiterating that most of our life in Christ is essentially penitential, Varden recalls the importance of the ashes on Ash Wednesday at the beginning of Lent. It establishes, he says, a ‘kinship with this world of dust,’ and our ‘readiness to abdicate pretensions to omnipotence,’ and that ‘standing before God in this way, I profess that I am not God. I admit the chasm that separates me from him.’ (p.15) God formed Adam from dust (Adamah in Hebrew) and breathed life into him. In order to be ‘re-formed’ in Christ we need to make ourselves dust again. That is why St. Benedict in his Rule accentuates the idea of humility, with our lives being a climb towards greater and greater humility by way of a ladder (echoing Jacob’s stairway to heaven dream in Genesis 28). St. Bernard reinforces this by a focus on the possibility of descending the ladder too, in his ‘Steps of Humility and Pride.’

In the book Varden talks about his kinship with the existential philosopher and poet Stig Dagerman whose ‘resolute nihilism…kept him balancing on a precipice that reached out over a menacing void.’ (p.25). He relates this to reading an account, by the Soviet Army correspondent Vassily Grossman, of the hell of Treblinka, where the Nazis tried to cover their tracks by digging up the bodies of murdered Jews, burning them and scattering the ashes on roads near to the camp. Varden talks of Dagerman having come of age during the aftermath of the second world war and describes his knowledge of the wages of war as an ‘open wound on his heart.’ Dagerman took his own life in 1954 at the age of 31.

This perception of the enormity and futility of life I once again encountered in a vivid way when I was around 17 years old. This enormity and my smallness was met by the ‘what’s it all for’ question. Plagued by bouts of depression, I found myself alone in the beautiful Kent countryside. Near where we were living was a big stretch of common land called a ‘Minnis.’ The night sky was perfectly clear and I lay down on the ground and gazed upwards. The vastness of the universe was terrifying and echoed my personal emptiness and perception of the world about me. And yet at the same time it was completely full – full of bright shining stars, offering light. There was so much more to be had than that which I previously understood, I was made for more. Something was inviting me on a journey and I agreed to take it. There was more, and here was my ladder being offered as a way to cross the void. A glimpse of the transcendent reality lifted me and placed me on that ladder. And so began my journey towards God.

Varden’s declared kinship with Dagerman is empathic to the universal experience of emotional and spiritual darkness. That chasm of meaninglessness that we all encounter at some point if we are open to the truth of what this life presents to us. The divergence with Dagerman is how Varden encounters and uses the ladder of faith to cross that chasm. He describes the ladder as being laid flat across the chasm, enabling us to scramble to the other side. The vertical ascent is the next step. Sometimes you just need to get to the other side. Sometimes you just need to get past chapter one. To trust that your own utter futility is leading you to trust in a power greater than yourself. This is why we need ‘God transcendent’ – The Almighty Father – The King – The Prince of Peace. To be awestruck by God’s total ‘otherness’ and to place ourselves at the mercy of that benevolent otherness. That it will lead, guide and protect us. Maybe this is why scripture tells us that the ‘fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom’ (Proverbs 9:10). And as Jesus said to St. Catherine of Siena, “Do you know who you are and who I am? If you know these two things, you will be blessed and the Enemy will never deceive you. I am He who is; and you are she who is not.” Maybe a little bit of fear, trembling and awe, coupled with a steady ladder to climb, is what we need to get past chapter one.

Dagerman looked into that abyss. I also looked into it. The call directed to us both is to raise our soul’s eyes to glimpse the other side; then to realize that, in Christ, a passage exists. The ladder of humility, laid flat, carries across. To own that I am dust is an act of daring. By that admission, I make peace with my poverty. I resolve to dwell within it. I accept that, for all my desire to live, I shall die; that I am dust with a nostalgia for glory. I am taught to let glory, by grace, lay claim to my being even now, to make it resonant with music of eternity. I learn to look towards eternity as home. It takes magnanimity to live on such terms, with such intensity. A monastery is a specialist environment designed to support perseverance over time. It is a place where the depths can be faced in Jesus Christ. It stands by its very existence as an extended hand of friendship to all who have looked into those depths and found them fearful.

Erik Varden o.c.s.o.

‘The Shattering of Loneliness’ p.32-33